By Kaisheng Wu

Among economists, carbon pricing mechanisms have often been touted as a singularly effective policy response to climate change. As such, the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) has been prioritised as the country’s key tool in meeting climate targets.

Climate Change Minister, James Shaw, recently stated in April of this year that “a well-designed system for pricing emissions is a central part of our Government’s climate change policy framework”.1 Just a month later, Lawyers for Climate Action NZ sought to take the minister to court over the cabinet’s decision to ‘water down’ NZ ETS.2 Conversely, NZ ETS and other carbon pricing attempts have consistently faced pushback from the agricultural sector.

In light of controversy surrounding NZ ETS, how does the government try to balance economic well-being, equity and climate goals using ETS?

The Logic of ETS

The emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) incurs a cost to society and to the environment. Yet the cost incurred by the public is not borne by emitters of GHGs. Without any policy interventions, emitters have no economic incentive to rein in their emissions profile.

By placing a value on emissions, either through a carbon tax or through an emissions trading scheme, governments are able to incorporate the social cost of emissions into the investment decisions of polluters—thereby limiting emissions volumes, as well as incentivising innovation for less carbon intensive activities.

How it Works

ETS Units and Revenue

The ETS requires emitters to ‘surrender’ one ‘New Zealand Unit’ (NZU) per tonne of carbon dioxide or equivalent (CO2e) to the New Zealand government.3 Participants are obligated to acquire NZUs by either, receiving units for free (free allocation), or buying units from other participants, or buying them at government auctions, or earning units by emissions removal – such as through planting trees, or buying them from external offset mechanisms or through international trade.

NZUs are currently priced around $52/CO2e. For reference, the production of a litre of milk in New Zealand causes an emission of 1kg of CO2e, if agriculture were to be fully incorporated into NZ ETS, the carbon price of a litre of milk would be about half a cent.

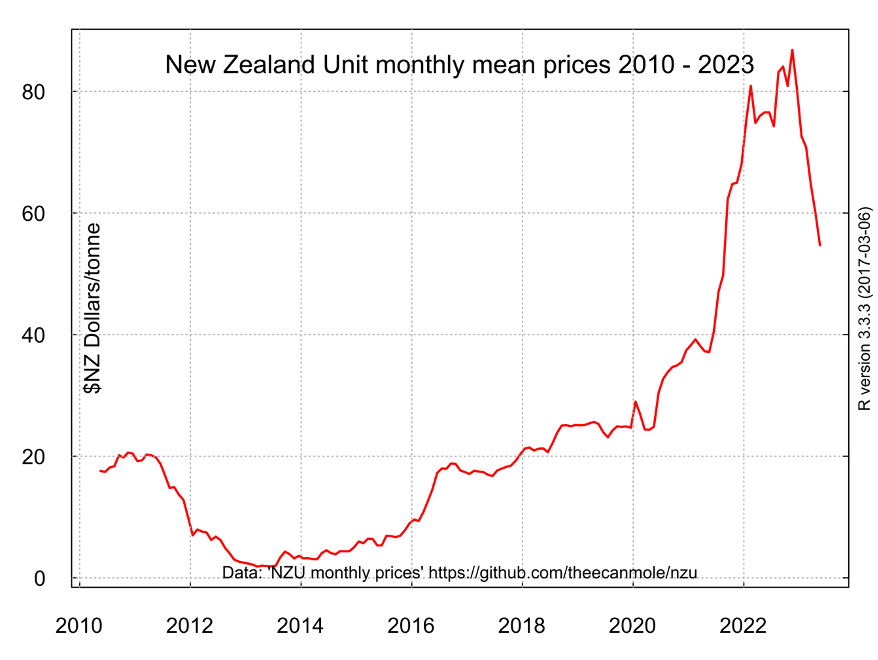

Historical NZU prices

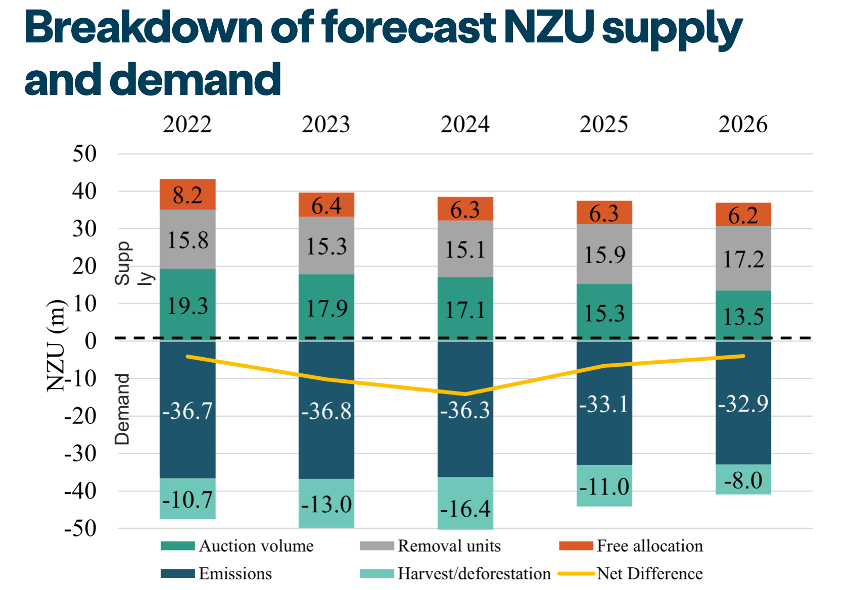

In order to reduce emissions, the ETS cap and supply of NZUs is designed to decrease over time – with unit supply being decided 5 years in advance. As seen in figure 3, the forecast supply of NZUs for 2023 is 39.6 million units. There is predicted to be significant demand-supply gaps in the coming years. If the gap causes prices to become too high, additional reserved NZUs are supplied to the market – and the New Zealand government is obligated to offset the additional emissions.

Revenue from NZU auctions are nominally funnelled into public investment in climate change initiatives – for example in 2021, the government used $4.5 billion of NZ ETS revenue to fund the Climate Emergency Response fund (CERF) and the Sovereign Green Bond programme.4 The CERF funds initiatives such as clean vehicle schemes and native afforestation schemes.5

2022 – 2026 NZU forecast

Sectoral coverage

The following sectors are affected by NZ ETS: forestry, stationary energy (electricity/heat), transport, industrial processes, synthetic GHGs, and waste. These sectors are obligated to both report emissions and surrender ETS emission units to the government annually by the end of June. The agricultural sector currently only has obligations to report emissions.

The government also identifies at-risk producers which are allocated free NZUs, free allocation is given to producers which have a high dependence on emissions (a high ratio of CO2e to revenue is deemed to be more than 1600t CO2e/million NZD) or to producers exposed to international trade – presumably with the view of preserving competitiveness.6 Free allocation has been planned to gradually reduce over time from 90% free allocation of NZU (2005) to at risk producers to 0% by 2050.

So who does the ‘surrendering’?

NZ ETS is designed to spread the cost of emission units across the entire supply chain, however only certain parties are obligated to ‘surrender’ NZUs at the end of the return period (30 June). These parties, or points of obligation, are selected with the view of keeping compliance and administration costs as low as possible, for example for the waste sector, the point of obligation are landfill operators.

The Exception to the Rule – A Brief History

In response to the Kyoto Protocol, New Zealand’s fifth Labour Government passed the Climate Change Response Act 2002, (CCRA) providing legal framework for climate action in New Zealand.7 Prior to NZ ETS, there were multiple failed attempts to legislate carbon pricing mechanisms, for example, in 2003 the government attempted to impose a methane tax on farms – but met significant public opposition in the form of ‘Fart Tax’ protests (misleadingly labelled because methane emissions from livestock are mostly through burping).

Bill English at a 2003 ‘Fart Tax’ protest at the steps of Parliament

Eventually, via amendment to the CCRA, NZ ETS was implemented in 2008. Sectors were progressively incorporated into the scheme – by 2013, only the agricultural sector was exempt from NZ ETS. In June of 2020, the government amended the CCRA to require methane and nitrous oxide emissions to face a carbon price by 2025.8

Finally, in October of 2022, in partnership between farmers, industry groups, iwi, the MPI and Environment ministries (He Waka Eke Noa), an alternative scheme to price agricultural emissions was agreed upon.9 The carbon price was significantly lower than NZ ETS prices, at $3.93/t CO2e. The response from sector groups such as Federated Farmers has been dismissive: suggesting the scheme would “rip the guts out of small town New Zealand, putting trees where farms used to be”.11

The future of ETS? Recent scepticism toward carbon pricing

Though perhaps misapplied, concerns about forestry replacing farmlands are not entirely unfounded. In 2022, spikes in the price of NZ ETS lead to concerns of the displacement of pastures with so called ‘carbon farms’ – afforestation with the view of generating NZ ETS credits.12 At NZU prices of $80, carbon farms generate revenue of upwards of $1000 per acre annually compared to around $160/acre for livestock ranches, creating concerns about “green deserts” – the comparative lack of job generation associated with forestry (1 job/2,500 acres vs 13 jobs/2,500 acres for livestock farming).

More broadly, prevailing carbon pricing economics scholarship by William Nordhaus has come under criticism for underestimating climate change damages, as well as for discount rates that are too high (discounting the harm borne by future generations).13 Combined with increased urgency surrounding the accelerating and less predictable impacts of climate change, a shift in public policy has occurred in favour of technological incentives and subsidies – as reflected in the $392 billion in climate subsidies seen in the passage of the Biden Administrations Inflation Reduction Act.

As such, carbon pricing mechanisms remain an important tool in addressing climate change – but at the very least it can be said that schemes such as NZ ETS are no longer the panacea for climate change response that they once were – both in terms of their importance in reducing emissions and in terms of their sustainability impacts generally.

[5] https://www.budget.govt.nz/budget/2022/wellbeing/climate-change/summary.htm

[7] https://environment.govt.nz/acts-and-regulations/acts/climate-change-response-act-2002/

[8] https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/news/new-zealand-passes-legislation-finalizing-ets-reforms

[11] https://www.fedsnews.co.nz/governments-farm-emissions-plan-say-goodbye-small-town-new-zealand/

[12] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/11/business/new-zealand-carbon-farming.html

[13] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/business/economy/economy-climate-change.html